Investigating how technology-focused academic fields become self-sustaining

This is a report on a project undertaken by Megan Kinniment and me to investigate the question “how do academic fields that aim to develop a technology grow into self-sustaining fields”. In the report, “we” usually refers to things Megan and I did / believe etc, while “I” refers to things I did / believe etc (see this report on the Effective Altruism Forum here).

See this report on the Effective Altruism Forum here.

Summary

We undertook a research project attempting to shed light on the question “how do academic fields that aim to develop a technology grow to become self-sustaining?”.

We define a self-sustaining field as “an academic research field that is capable of attracting the necessary funds and expertise for future work without reliance on a particular small group of people or funding sources” (see here for more).

Shedding light on our research question seems useful for forecasting technological development and important for doing differential technological development, especially for technologies that are highly ambitious. Progress in these areas seems potentially highly impactful from a longtermist perspective.

We looked at the histories of 10 academic fields that had developing a technology as their main goal. The fields we looked at include Fusion Power, RNA Vaccines, and AI. In choosing fields, we aimed for a sample representative of the kinds of emerging fields that might be important to think about today or in the near future: we preferred well-defined fields with a clear technological goal and where the academic field plays a significant role in developing the technology, and we tended to favour current or relatively recent fields. We also favoured relatively large fields, partly because this made data collection easier (see here for more on which fields we chose and why).

For each of these fields, we recorded binary time series of 29 factors (e.g. “prestigious advocate” and “early prototypes exist”)1 that seemed relevant for field development, and came to a judgement about when each field became self-sustaining (if it did). The factors were chosen following a literature review and initial explorations of the histories of several fields (more on the data collection here).

Note that I’m unsure how much the findings for the 10 fields we considered generalise to other technology fields (see here for more). I’d also highlight that, although we’re often most interested in causation, the relationships we’ve found aren’t enough to establish causation.

In the below and in the rest of the report, I use the following terminology:

- I use “field” (or sometimes “technology field”) as a shorthand for “academic field aiming to develop a technology”; these are the kinds of fields to have in mind while reading this report.

- I use “field establishment” (or sometimes just “establishment”) as a shorthand for “the field becoming self-sustaining”.

Here are our main findings:

- Within our dataset, we found that the “factor count”, defined as the number of factors that are switched on for a field at a given time, is strongly related to whether a field is self-sustaining (more here), and that the factor count in the preceding year is positively related to whether a field is about to become self-sustaining if it isn’t already (more here).

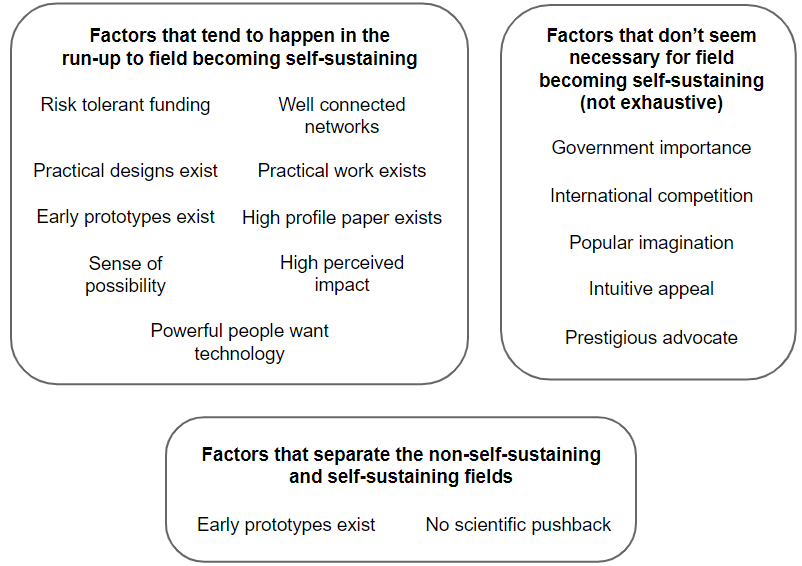

- We also found that some things tend to happen in the 20 years leading up to field establishment: risk tolerant funding becomes available, practical designs are made and practical work is done, early prototypes are developed, networks of researchers are formed, often a key paper is published, there’s often a sense that progress is possible and would be impactful, and there are often well-resourced individuals who want to see the technology happen (more here).

- On the other hand, factors that didn’t seem necessary for field establishment in our dataset include: the existence of a prestigious advocate, international competition, the technology being easy to capture people’s imaginations with, the technology being generally known about, and perceptions of particular importance from governments (more here).

-

The two obvious things that separate the 2 non-self-sustaining fields we looked at from the 8 self-sustaining fields are mainstream scientific pushback and a lack of prototypes (though selection effects might make generalising from this result especially difficult2) (more here).

- The results described in the preceding 3 bullet points are summarised in this figure:

-

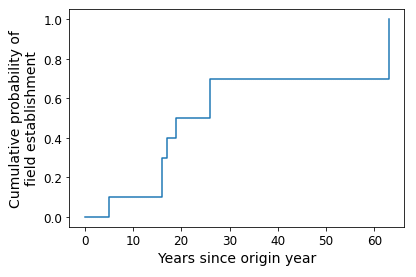

For the 8 fields that reached establishment, the median time between a field’s origin year and establishment year3 was 18 years, with the quickest field (Genetic Circuits) becoming established after 5 years, and the slowest (Clean Meat) becoming established after 63 years (the full list of times to establishment for the 8 fields, in years, is: 5, 16, 16, 17, 19, 26, 26, 63). Of the 2 non-established fields, at the time of writing one has had 31 years since its origin year, and the other has had 40 (more here).

- But note that this is probably very sensitive to the particular fields we chose to consider: for example, we may have tended to look at “big” fields that take particularly long to become self-sustaining.

Guide to the rest of the report

The structure of the rest of the report is described in the bullet points below. I’d suggest that most readers who want to read beyond the summary should skim the Research question, context, and motivation and The data we collected sections for an understanding of the project, and then skim the Prediction takeaways and Differential technological development takeaways sections for more takeaways. Some readers might also find the brief opinionated stories about field establishment particularly interesting.

- The next two sections describe the research question, context, and motivation and the data we collected for the project. The latter section includes things to keep in mind when drawing inferences from the data.

- The two sections after that contain more detailed takeaways than the ones provided above in the summary: Prediction takeaways, Differential technological development takeaways

- The section after that contains our brief opinionated stories about field establishment. This is a standalone “qualitative” section that some might find interesting.

- The section after that contains the detailed results, including those underlying the various takeaways. Both quantitative results and qualitative results (e.g. subjective themes we drew out of our reading about field histories) are included.

- Finally, More details provides links to various Google Docs with the raw data, definitions, and further writing related to the project, and Final thoughts briefly wraps up and mentions some directions for future work.

- (The Appendix contains more results that didn’t make it into the main text; each is linked at least once from the main text).

Research question, context, and motivation

The aim of the project was to shed light on the question “how do academic fields that aim to develop a technology grow into self-sustaining fields”. We define a self-sustaining field as “an academic research field that is capable of attracting the necessary funds and expertise for future work without reliance on a particular small group of people or funding sources” (see the next subsection for more on this definition).

As noted in the summary, I use the following terminology in this report:

- I use “field” (or sometimes “technology field”) as a shorthand for “academic field aiming to develop a technology”; these are the kinds of fields to have in mind while reading this report.

- I use “field establishment” (or sometimes just “establishment”) as a shorthand for “the field becoming self-sustaining”.

We addressed our research question by looking at the history of 10 academic fields that each aim to develop a particular technology. Of these 10 fields, we consider 8 to have become self-sustaining at some point. For each field, we recorded a timeline of important events, subjective descriptions of how the field developed, binary time series for each of 29 factors that we considered potentially important for field development, and our judgement for when the field became self-sustaining. I’ll expand on this in the next top-level section. The quantitative data, timelines and development descriptions can be found here.

Defining “self-sustaining”

To give a bit more of a feeling for how we think about the concept of a field being self-sustaining, the core elements by our definition are:

- An expectation of consistent funding from diverse sources

- Many research groups consistently requesting funding for work in the area

- A clear identity for the field (a group of researchers with shared goals and foundational knowledge, and with agreement on main problems)

Some elements that are not core but are (at least) often the case are:

- A respectable, decently sized, mainstream field

- Funding from multiple governments

And here are some examples (note that these claims are our impressions from learning about the histories of these fields; we are not necessarily confident that every claim is accurate):

- Not self-sustaining: Quantum Computing in 1993, just before Shor’s algorithm was published. There was some ongoing theoretical work on quantum computers, apparently funded by theoretical physics institutes or other funding sources for basic science. We think that the amount of research activity and funding at this time weren’t enough to make this a self-sustaining field.

- Self-sustaining: Quantum Computing in 1996, a couple of years after Shor’s algorithm. The technology was now seen as strategically important and (various parts of) the US government had just begun organising workshops and putting out calls for research proposals. The first experimental realisation of a quantum logic gate had also recently been made. At this point, the field seems self-sustaining to us.

- Not self-sustaining: Clean Meat in 2010. A roadmap to large-scale manufacturing of Clean Meat had been put out 5 years earlier, receiving lots of media attention and some scientific interest, and in 2009 cultured meat was cited as one of the 50 breakthrough ideas of 2009 by Time magazine. On the other hand, the Dutch government had recently cut its funding after being a major funding source for many years. We think the field could still have faded into obscurity from here (though it’s fairly borderline).

- Self-sustaining: Clean Meat in 2013. In 2013, Mark Post presented his Clean Meat hamburger for tasting at a televised event. Apparently this was a bit of a watershed moment, greatly increasing public awareness of Clean Meat and reducing its perceived “ick factor”. Some of the first Clean Meat startups were launched from 2011, and in 2012 it was reported that there were 30 labs working on Clean Meat research. At this time the field seemed healthy and likely to continue to attract diverse funding, so we judged it to be self-sustaining.

Motivation for the project

The project seems valuable because getting a better understanding of how fields become self-sustaining can be helpful for forecasting technological development and doing differential technological development. Progress in these areas seems potentially highly impactful from a longtermist perspective

The question seems especially relevant for technologies that are highly ambitious, and where the private sector is unlikely to step in and invest until a significant amount of research has already been done. For technologies like this, it seems that the creation of a self-sustaining field that is aiming to develop the technology could make a huge difference to the prospects for the technology’s development.

In general, I’m aware of theories or stories regarding why particular fields developed when they did (or failed to develop). These can often seem quite convincing, but I find it hard to know for any particular story whether there are factors that get left out of the picture despite being vitally important, for example because they’re less salient (think incremental progress in some precursor technology vs a prominent government programme or public advocacy from a high-prestige individual). The approach we took with this project can be seen as an attempt to address this issue by creating a wide-ranging list of development factors and recording the status of each factor over time for each field. I hope that this allows for a more trustworthy and objective analysis.

The surrounding academic literature

I’m not an expert in this area and most of my knowledge of the literature comes from the literature review Megan performed at the start of the project.

The areas of the academic literature that seem to be most relevant for our research question are Scientometrics and Science of Science.4 The relevant work in these areas tends to focus on using bibliometric data (e.g. citation graphs) to study emerging academic fields, for example identifying research fields that are likely to grow rapidly on a ~5 year time horizon. These methods generally seem at least partially successful, apparently performing significantly better than chance when performance is assessed.5

We weren’t able to find any studies that had quite the focus we were interested in, namely a focus on when relatively large fields that are explicitly trying to develop a technology become self-sustaining (as we define that term), using “real-world” factors rather than bibliometric data.

This post on the Effective Altruism forum by Megan contains some general takeaways from the literature review she performed for this project.

The data we collected

We considered 10 technologies and their corresponding fields: AI, Atomically Precise Manufacturing, Clean Meat, DNA Nanotechnology, Genetic Circuits, Quantum Computing, RNA Vaccines, Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence, Solid State Batteries, and Fusion Power.

When choosing technologies, we wanted a sample representative of the kinds of important emerging technologies that would be helpful for understanding the development of academic fields today for the purposes of technology forecasting and differential technological development. We wanted technologies that had a significant academic field associated with them (or might do so in the future), that were well-defined, and for which “success” had a clear end-point. We generally favoured more recent fields (although we also wanted some diversity in recency). For more on how we chose the technologies, see this Google Doc.

For the academic field associated with each of these technologies, we recorded

- a timeline of important events,

- narrative descriptions and our own opinions regarding how the field developed,

-

binary time series6 for 29 factors that we thought might positively influence field development ,

-

the “origin year”, defined as the year the technology was deliberately explored for the first time,7

- the “establishment year”, defined as the year the field first became self-sustaining, if applicable.

Both the qualitative and the quantitative data were mostly collected using Wikipedia and googling, often leading to skimming papers or books, as well as using our pre-existing knowledge about the fields where applicable. We usually spent roughly 10-20 hours collecting the data for a field (5-6 hours for the two fields we had good pre-existing knowledge of). It was often necessary to use our judgement to determine the status of the factors and the year the field became self-sustaining; often this was fairly ambiguous (although in many cases I think any reasonable choice would give similar results; see Sensitivity analyses suggest that the logistic regression of establishment year against factor count is robust to exact choice of fields and establishment years, but also Plotting the logistic regression R-squareds against factor lag arguably provides weak evidence that our establishment year judgements are biased).

We chose the 29 factors according to what we thought might be positively associated with field development,8 following a literature review and initial explorations of the histories of a smaller number of research fields.

Here are some of the factors along with their definitions:

- Risk tolerant funding: At this time, there was in total more than $1mil per year (1990 USD equivalent) of risk tolerant funding going towards the development of this area or technology. Where risk tolerant funding is funding where it is accepted that failure is at least somewhat likely and that this is an acceptable outcome.

- High perceived impact: At the time, this technology was seen as a potential game changer. This could either be by scientists, policy makers, or the public.

- Early prototypes exist: By this time, a physical device exists whose purpose is to make progress towards the target technology, and contains at least some aspect of the functionality of the full technology (even if it is not otherwise functional). (e.g an early “fusion reactor” that can produce fusion reactions but far far fewer than necessary for a power producing device)

- Intuitive appeal: If someone with present day (2021) knowledge were to explain the idea of this technology to people at this time, it would be easy to capture people’s imaginations by e.g. explaining the positive effects it will have for society.

- Government importance: At this time there are government documents discussing this area / technology and its potential impact OR at this time research programs were funded by governments on this area / tech.

- No scientific pushback: At this time, neither prestigious critics nor general scientific establishment pushback were noted by researchers or experts in this area (then or afterwards).

A list of all 29 factors with descriptions can be found in this Google Doc. For each factor and for each research field, we recorded whether it was “on” or “off” for each year in the history window (in most cases 1920-2020).

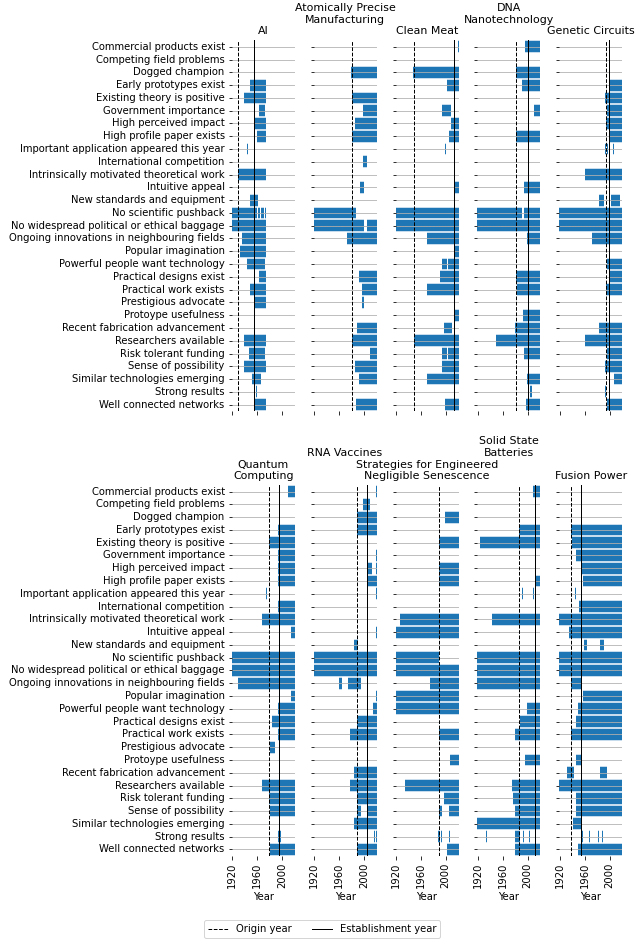

Here is a representation of the entire quantitative dataset (this is just for illustration; feel free to only glance at it):

There’s one panel for each of the 10 fields we looked at. Each row corresponds to the status of a particular factor for that field at a particular time (note that for AI the data only runs until 1974). The origin year and the establishment year for each field are shown with dashed and solid vertical black lines, respectively.

See the section below, More details, for links to the quantitative dataset and the field development timelines and descriptions we wrote during this project.

Possible sources of bias and other issues

Data collection

The view we get by systematically recording the status over time of a wide range of factors for each field has the potential to be more objective than the view obtained directly from reading histories or timelines of field development. However, the quantitative data we collected (factors, origin year, establishment year) still relies on human judgement to a significant extent.

Most notably, for each field, the factor statuses and the establishment year were recorded by the same person. Since for a given field there are often a range of years that seem reasonable candidates for the establishment year, it seems plausible that there’s an inclination (whether conscious or unconscious) to favour years where several factors switch on as the establishment year. This would make factors appear to be more closely related to the “true” establishment year than they really are. Because of this worry, I’ve avoided presenting results that seem very sensitive to the exact choice of establishment year (see Plotting the logistic regression R-squareds against factor lag arguably provides weak evidence that our establishment year judgements are biased for an inconclusive attempt to investigate whether this bias exists).

In addition, when determining the factor statuses we relied on relatively shallow investigations, and factors we couldn’t find positive evidence for would often be recorded as a “no”. I’d expect that more thorough investigations would result in more factors being a “yes” for a given field and year, and that fields that have better documented histories (e.g. Fusion Power) will have more “yes” entries, all else equal.

Finally, in many cases we weren’t able to gather much information in the time available and were forced to record factor data on a best-guess basis – aside from this adding noise to the data, this may have also introduced biases that aren’t immediately obvious.

Having said all this, for the sensitivity checks and other analyses I’ve performed, the relevant results seem fairly robust. See Sensitivity analyses suggest that the logistic regression of establishment year against factor count is robust to exact choice of fields and establishment years and The distribution of factor first occurrences within the breakout period isn’t just due to noise for more information about these.

Technology selection bias and generalisability

I think that selection bias regarding the choice of technologies to look at should be a key consideration when attempting to draw generally applicable lessons from this work. The particular technologies we chose to look at are partly a reflection of the kinds of technologies and fields Megan and I know about or were able to easily find information about by searching online or asking people in our networks.

This seems particularly important for the two fields we looked at that (we think) haven’t become self-sustaining, and so aren’t necessarily as well known as the others, namely Atomically Precise Manufacturing and Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence. We found it hard to identify and find data for fields that made some progress towards being self-sustaining but never achieved self-sustaining status, and the choice to look at these two technologies probably reflects our exposure to the EA, rationalist, and futurist communities. For example, maybe technologies encountered through these communities are especially likely to be highly ambitious and to experience pushback from mainstream science.

This being the case, I think the safest way to start off thinking about results from the data we collected is “for these 10 technology fields, our data shows…”, rather than “for technology fields in general, our data shows…”. From there, you can think carefully about the extent to which you expect the results to generalise to technology fields in general or to the particular fields you might be interested in.

Factors that are switched on when a field is self-sustaining (almost) by definition

As a reminder, we define a self-sustaining field as “an academic research field that is capable of attracting the necessary funds and expertise for future work without reliance on a particular small group of people or funding sources”. Some factors seem (at least) close to being “switched on by definition” when a field is self-sustaining. These are:

- Risk tolerant funding

- Definition: At this time, there was in total more than $1mil per year (1990 USD equivalent) of risk tolerant funding going towards the development of this area or technology. Where risk tolerant funding is funding where it is accepted that failure is at least somewhat likely and that this is an acceptable outcome.

- Explanation: While it seems possible for a field to be “capable of attracting the necessary funds for future work without reliance on a particular small group of funding sources” without this factor being switched on, the two are at least very closely related.

- Researchers available

- Definition: At this time, either there are researchers working directly in this field OR if not, there are researchers in neighbouring fields who would be a decent fit for work in this field if they were to work on it. Concretely: If a government or funding body wanted to develop this area, they have researchers to turn to in the field already, or they know which neighbouring fields contain researchers with a good fit.

- Explanation: This is on by definition if researchers are working in this field, so presumably it must be on if the field is self-sustaining.

- Well connected networks

- Definition: At this time there is at least a small number of researchers (very roughly, at least 5) interested in this area who are in fairly regular contact.

- Explanation: It seems hard to imagine a self-sustaining field that doesn’t have a group of at least 5 researchers in contact with each other.

For these 3 factors, finding that they tend to be switched on by the time field establishment happens probably doesn’t provide very useful information by itself. These factors still seem useful, however: for example, it might be interesting to know what the lag tends to be between “risk tolerant funding” switching on and field establishment.

Prediction takeaways

There are clear patterns in the statuses of the 29 factors in the years leading up to field establishment. While there is a lot of noise, it seems likely that at least some of these represent real relationships and effects for fields that are sufficiently similar to the 10 fields considered in this project.

One general trend is that the “factor count”, defined as the number of factors that are switched on for a field at a given time, is strongly related to whether a field is self-sustaining, and the factor count in the preceding year is positively related to whether a field is about to become self-sustaining if it isn’t already.

- I’d tentatively suggest that, roughly speaking, if you only know a field’s factor count, it’s unlikely to become self-sustaining next year if its factor count is below 13, and potentially quite likely to become self-sustaining next year if its factor count is above 20 (but for example, if the field has had a high factor count for a long time without becoming self-sustaining, I’d be much less confident that a high factor count implies that it is likely to become self-sustaining next year).

- It appears to be possible to forecast future factor counts for a field based on past factor counts with some accuracy, which would allow for longer-ranged forecasting of field establishment, although I haven’t looked into this (see Factor count dynamics for plots of the factor count time series).

Regarding individual factors:

- Some factors tend to switch on in the 20 years leading up to field establishment (each of these were switched on by establishment for at least 6 of the 8 established fields we looked at, having been mostly switched off 20 years before establishment): risk tolerant funding becomes available, practical designs are made and practical work is done, early prototypes are developed, networks of researchers are formed, often a key paper is published, there’s often a sense that progress is possible and would be impactful, and there are often well-resourced individuals who want to see the technology happen.

- In addition, relevant fabrication advances often (for 5 out of 8 fields) happen roughly 10-25 years before establishment.

- Statistical analyses also suggest that certain factors from this group are important for field establishment, especially the existence of early prototypes, publication of strong results, and high perceived impact; although I take these analyses as providing very weak evidence.

- These analyses also suggest that some things may be helpful for field development despite apparently not being necessary, namely the publication of strong results, the development of commercial products, and a commercially viable product being within relatively close reach (accessible within roughly 10 years by a group of 10 researchers).

- Other factors that don’t seem necessary for field establishment include: the existence of a prestigious advocate, international competition, the technology being easy to capture people’s imaginations with, the technology being generally known about, and perceptions of particular importance from governments.

- Mainstream scientific pushback and a lack of prototypes are two obvious things that separate the 2 non-self-sustaining fields we looked at from the 8 self-sustaining fields (though selection effects might make generalising from this result especially difficult).

For the 8 fields that reached establishment, the median time between a field’s origin year and establishment year was 18 years, with the quickest field (Genetic Circuits) becoming established after 5 years, and the slowest (Clean Meat) becoming established after 63 years. Of the 2 non-established fields, at the time of writing one has had 31 years since its origin year, and the other has had 40.

Differential technological development takeaways

Generally, to generate takeaways for differential technological development it’s necessary to identify causation; this is pretty hard in general, and especially so for this project because we only have observational data.

Still, here are some tentative takeaways:

-

We defined a factor called “risk tolerant funding”, corresponding to consistent funding of roughly $2million per year or more from sources that accept a high risk of failure (this is usually government funding, including basic science funding).9,10 All 8 fields that have become self-sustaining in our dataset had funding of this kind before establishment, but in some cases there was a lag of more than 10 years between this funding first appearing and the field becoming self-sustaining; and in addition, the 2 fields in our dataset that aren’t self-sustaining have had funding of this kind for a decade or more. This result doesn’t prove that risk tolerant funding is unimportant, but it suggests to me that risk tolerant funding isn’t sufficient for a field to become self-sustaining.

- I think that the positive relationship between factor count and field establishment pushes a bit away from the idea that there’s a key highly targeted intervention that promotes field establishment and a bit towards the idea that many top interventions are similarly effective, that many types of intervention are necessary, and that interventions that influence a broad range of factors are particularly effective.

- Very tentatively, maybe this result also pushes a bit towards looking for “weak areas” among the 29 factors and boosting those in order to promote field establishment; especially the factors that are usually switched on by the establishment year for the fields we looked at.

- The data provides (weak) evidence that avoiding mainstream scientific pushback is important, as we might already suspect: we judged the 2 non-self-sustaining fields we looked at to be experiencing mainstream scientific pushback, whereas the 8 self-sustaining fields were not when they became self-sustaining.

- I tentatively think that seeing certain factors tending to switch on in the run-up to field establishment should push us a bit towards thinking that they have a causal effect on field establishment, implying that interventions that cause these factors to turn on might be good for field establishment.

- As I noted in the “prediction takeaways”, the things that tend to happen in the ~20 years leading up to field establishment are: risk tolerant funding becomes available, practical designs are made and practical work is done, early prototypes are developed, networks of researchers are formed, often a key paper is published, there’s often a sense that progress is possible and would be impactful, and there are often well-resourced individuals who want to see the technology happen. In addition, relevant fabrication advances often happen roughly 10-25 years before establishment.

- Some of these factors also appear particularly important based on statistical analyses, most notably the existence of early prototypes, publication of strong results, and high perceived impact, although I take this as very weak evidence for their importance.

I think that someone very interested in promoting the development of a particular field could also find looking at our qualitative summaries of development and timelines for each field useful. See the next section, a later section with more detailed development stories, and More details for further links.

Brief opinionated stories about field establishment

The following list summarises our “opinionated stories” describing the main developments that led each field to become self-sustaining. These should be treated as speculative. They are attempts by us, as non-experts, to distill the key reasons the field became self-sustaining when it did, further compressed to a couple of bullet points per field.

See this later section for the full “opinionated stories”. Our takeaways from these stories (and, more broadly, from reading about the 10 fields) are given in this later section. Notes on each field’s development that are much expansive but much rougher can be found in this Google Drive folder.

- AI

- Advances in our understanding of the brain and the development of computers made artificial brains a natural next step (~1940s).

- Early successes with computers (e.g. WW2) led militaries to become interested in investing in the area.

- Clean Meat

- Advances in tissue engineering made this possible (~1950s-2000s).

- A few believers pushed for it to happen (1950s-2010s).

- DNA Nanotechnology

- A dogged champion generated good results over decades (1980s-2000s), until enough good directions had opened up for other people to get stuck in to.

- Fusion Power

- High expectations were set by rapid progress in fission research (~1940s).

- A false news report created a perception that states were behind the curve (1951).

- Genetic Circuits

- New experimental techniques and theoretical understanding made the field possible (~1970s-1990s).

- Targeted government funding played a role later on (~1990s).

- Quantum Computing

- Feynman’s public interest probably helped initially (~1980s).

- Discovery of Shor’s algorithm triggered huge interest (1994).

- RNA Vaccines

- PCR made it easier and strong initial results generated interest (1980s-1990s).

- Then unexpected safety issues caused a wilderness period, and these issues were eventually overcome due mostly to the efforts of two dedicated scientists (1990s-2000s).

- Solid State Batteries

- Small attempts were made in this area over many years due to the apparent advantages of this technology (1960s-1970s).

- As lithium batteries were being developed scientists realised that solid lithium batteries would be a big deal, galvanising efforts in this direction (1978).

Detailed results

Factor count is strongly related to whether a field is self-sustaining

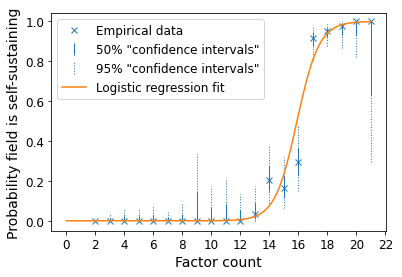

It turns out that the factor count corresponds fairly closely to the self-sustaining status of a field. Here is the empirical probability (i.e. according to our dataset taken at face value) that a field is self-sustaining in a particular year as a function of the factor count in that year:

I’ve included a logistic regression fit (essentially just fitting an s-curve), which fits the data fairly well. To give some idea regarding the amount of data underlying the empirical probabilities, I’ve included 95% (dotted lines) and 50% (solid lines) confidence intervals for these probabilities (these confidence intervals can give some idea of the statistical uncertainty but shouldn’t be taken too seriously / at face value11). There is a fairly sharp transition from ~factor count = 13 to factor count = 19 during which the field goes from being very unlikely to be self-sustaining to being very likely to be self-sustaining.12,13

I think this is an important validation of the data because it shows that factor count is closely related to whether a field is self-sustaining in our dataset. But, of course, in itself it’s not very useful: if you want to know whether a field is self-sustaining, you would probably prefer to check that directly by learning about the state of the field and making a judgement, rather than by collecting data on the 29 factors. It’s also not clear from this result whether a high factor count leads to a field becoming self-sustaining, or whether self-sustaining fields just tend to experience increasing factor count.

Factor count is positively related to whether / when a field becomes self-sustaining

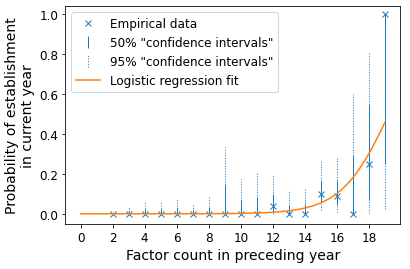

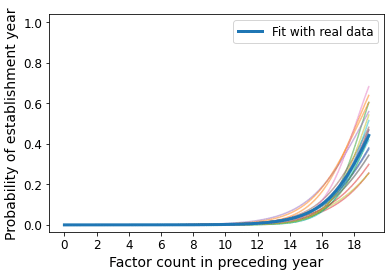

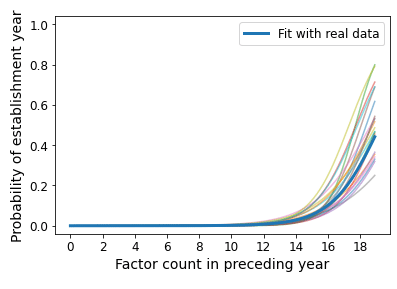

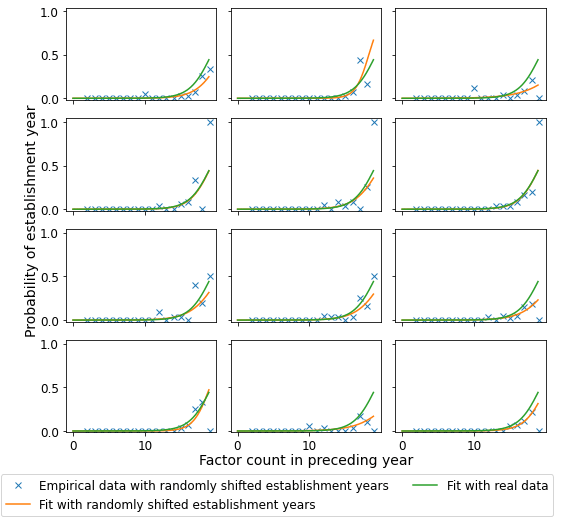

To assess whether the factor count is useful for prediction, it’s helpful to consider the probability that a given year is the establishment year (i.e. the first year the field is self-sustaining) as a function of factor count in the preceding year. I condition on the field having not already become self-sustaining by excluding years after the establishment year from the calculation. The results are plotted below.

As before, the error bars show 95% (dotted lines) and 50% (solid lines) confidence intervals under some set of assumptions (which, as before, shouldn’t be taken too seriously). There is a clear relationship between the empirical probability of establishment and the factor count in the preceding year, although the data is significantly more noisy than was the case for the previous plot.14

Despite the wide error bars, I think this shows that the factor count can be at least somewhat useful for predicting whether a field will become self-sustaining in the next year.

One approach to doing longer-range forecasting would be via forecasting the future factor count using the factor count’s recent history, although we haven’t tried to do this. Plots of factor count time series can be found in this section.

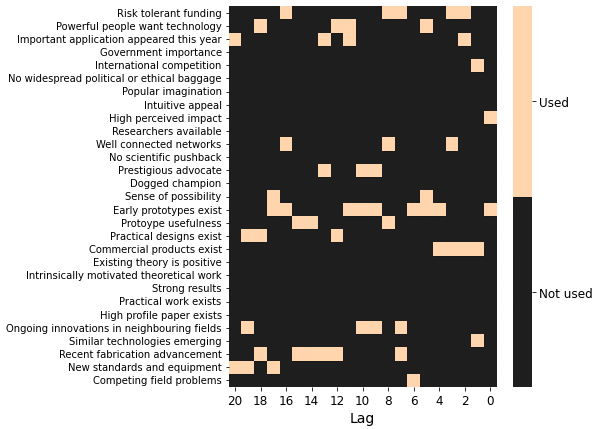

When the different factors tend to occur

Factor occurrences in the run-up to establishment

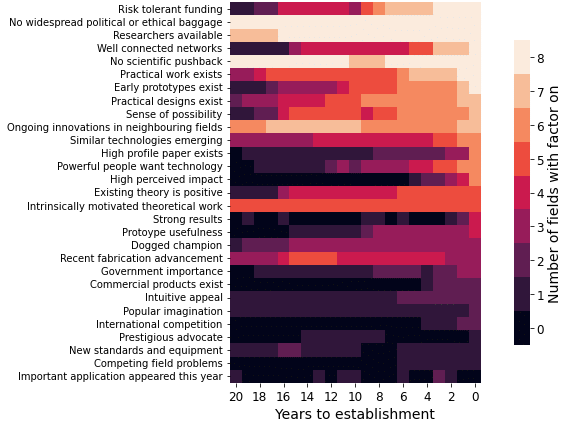

The plot below shows how many of the 8 fields that became self-sustaining in our dataset had each factor switched on in the 20 years leading up to field establishment, as a function of time to establishment. Lighter colours correspond to the factor being switched on for more fields. The factors appear in order from high to low corresponding to the number of fields for which the factor is switched on in the establishment year.15

A rapid change in colour from left to right indicates that the factor goes from being switched off for most fields to switched on for most fields in the years leading up to establishment, suggesting that it might be especially relevant for field establishment (these tend to be in the top half of the plot). Factors for which this is true include “risk tolerant funding”, “practical work exists”, “early prototypes exist”, “well connected networks”, “practical designs exist”, “sense of possibility”, “high profile paper exists”, “high perceived impact”, and “powerful people want technology”. You might summarise these as “availability of funding, practical progress, sense that the technology is important (including among well-resourced individuals) and achievable, and existence of at least a small community of researchers”.

On the other hand, some factors are usually not switched on at establishment (lower third of the plot, dark colour on the right edge of the plot). I think that the following are especially interesting examples of this: “prestigious advocate”, “commercial products exist”, “international competition”, “intuitive appeal” (meaning roughly “the nature of the technology is such that it seems easy to capture people’s imaginations with it”), “popular imagination” (meaning roughly “people generally know what the technology is and don’t view it negatively”) and (to some extent) “government importance”. These seem like the kinds of things you’d think might be important for a field to become self-sustaining. But this result shows that, at least for some kinds of fields, these factors, as we’ve defined them, aren’t necessary for establishment (although of course the result is consistent with these factors being highly beneficial for field establishment).

I’m not sure how best to summarise the difference between these two groups of factors, but it seems like the factors in the first group (which tends to precede a field becoming self-sustaining) are in many cases quite concrete things like funding and practical progress, whereas the factors in the second group (which seems to not be necessary for field establishment) tend to be to do with how the technology is perceived and advocated for.

After seeing this result, I now think the factors in the second group are probably in some sense “harder to achieve” than those in the first group – it could be that they appear less often before establishment purely because they’re less important, but I think at least part of the story is that they are the kinds of things that generally happen less often and/or are harder to make happen (while still being important). This wasn’t obvious to me before starting this project.16

Finally, “recent fabrication advancement” is notable for peaking around 10-15 years before field establishment. This seems to roughly correspond to fabrication advances happening for more fields in the period 10-25 years before establishment than in the 10 years leading up to establishment.17 A story you could tell about this would be that fabrication advances allow further practical advances and create a sense that progress is possible, and these things in turn make field establishment more likely.

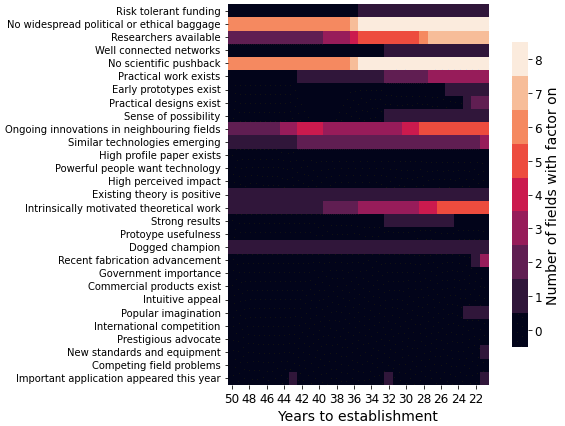

So far I’ve only presented the data in the 20 years leading up to establishment. It’s possible to look further back than this, although the data is a bit more sparse. The plot below shows the data for the period 21-50 years before establishment.

It seems that there’s often movement in nearby fields in this period, since the “similar technologies emerging”, “ongoing innovations in neighbouring fields”, and “researchers available” factors begin to switch on. “Intrinsically motivated theoretical work” also happens notably early (and the 0-20 year plot shows that, for these fields, the first intrinsically motivated theoretical work happens at least ~25 years before establishment).

(“No widespread political or ethical baggage” and “no scientific pushback” stand out as being switched on for all fields in this period (the darker colour / lower counts more than 35 years before establishment just reflect a lack of data for one or two fields). But maybe this isn’t very surprising because you wouldn’t necessarily expect pushback or baggage for fields in their very early stages.)

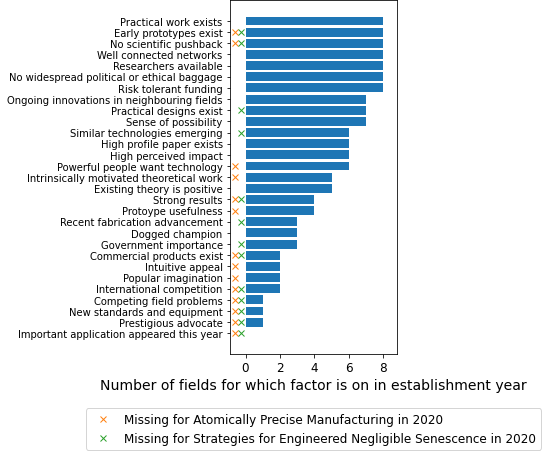

Factor occurrences in the establishment year compared to the non-self-sustaining fields in 2020

The plot below shows the number of fields for which each factor was switched on in the establishment year (equivalent to the right hand column in the first plot from the previous section), and also indicates the factor statuses in 2020 for the two fields in our dataset that are not self-sustaining fields, namely Atomically Precise Manufacturing and Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence.

By eye, the factor statuses for Atomically Precise Manufacturing and Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence seem fairly similar to those of the self-sustaining fields in their establishment years; there are lots of crosses in the lower half of the plot, which corresponds to the factors that are less frequently on in establishment years, and fewer crosses in the top half of the plot. However, notably, there are two factors absent for both Atomically Precise Manufacturing and Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence that are present for all 8 fields in their establishment years: “early prototypes exist” and “no scientific pushback”.

I take this as a weak suggestion that these two factors are important for field establishment. On the one hand, it seems unlikely that we’d see the absence of the same 2 factors for these 2 fields by chance. On the other hand, selection effects might be playing a significant role here: when choosing non-self-sustaining fields, we may have preferentially selected fields that were highly ambitious and experienced mainstream pushback, and the factor “early prototypes exist” could, for example, be serving as a proxy for “the goal is very ambitious and still far out of reach”.

Results from statistical measures of factor importance

I think that eyeballing the data as was done in the previous section is extremely useful, and it’s the source of a lot of the information I gained from analysing this dataset. In this section, I consider formal statistical techniques, specifically logistic regressions and decision trees. I think these are somewhat useful, because they give a slightly different angle on the data and are more objective.

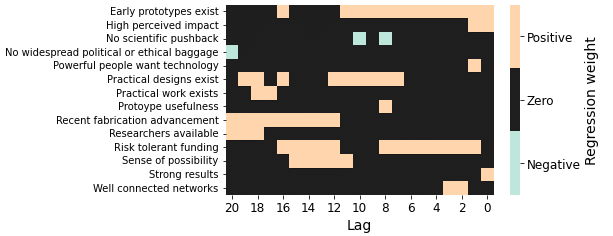

Roughly speaking, I ran logistic regressions with “is year Y the field’s establishment year” as the outcome variable and the factor values for a given year Y-A as the regressors, for various values of A. In other words, I ran a regression on the lagged factors for various lags.

With this data, overfitting is a significant concern. Partly because of this, I applied L1 regularisation for these logistic regressions. L1 regularisation also has the nice effect of giving many regressors a zero weight, essentially dropping them from the analysis.

Note that I excluded years after the establishment year for each field from the analysis, just like I did in the earlier section called Factor counts are positively related to whether / when a field becomes self-sustaining (to be a bit more precise, year Y was not allowed to take values greater than the establishment year).

The below plot shows the results of these regressions for lags ranging from 0 to 20 years. The plot indicates whether the lagged factors were given a positive, zero, or negative weight. Factors that are given a zero weight for all lags are not shown.

“Early prototypes exist”, “strong results”, and “high perceived impact” are given a positive weight in the lag 0 case, i.e. when using factor values to predict field establishment in the same year. “Early prototypes exist” is also used in regressions out to ~a 10 year lag. “Risk tolerant funding” gets positive weight at most lags, especially lags of less than 10 years (although not at zero lag). “Recent fabrication advancement” gets a non-zero weight for lags of between 12 and 20 years, presumably reflecting the fact that, as seen earlier, it’s unusual in having a substantial peak between 12 and 15 years before establishment.

In all cases, I think that the fact that these factors get a non-zero weight is suggestive that they’re useful for predicting field establishment (on a time horizon corresponding to the lag for which the non-zero weight was found).

A similar analysis using decision trees gives similar results,18 although with some differences. For example, “commercial products exist” seems more important for lags of between between 1 and 4 years. Again, I think this is suggestive that this factor is useful for prediction on the corresponding timescales.

Often, the factors that are picked out by these statistical methods are ones that were seen to vary a lot in the run-up to establishment in the Factor occurrences in the run-up to establishment section. This is the case for “early prototypes exist”, “high perceived impact”, and “risk tolerant funding”. On the other hand, some factors didn’t vary as much in the run-up to establishment but were still selected as being predictive, including “strong results”, and “commercial products exist”. For these last 2, this result suggests that these factors are useful for predicting field establishment despite not being necessary for establishment.

The length of time between field origin and establishment

One way to do a simple outside view-type forecast of when a field will become self-sustaining is to consider the number of years since the origin year.

In our dataset, for the 8 fields that reached establishment, the median time between a field’s origin year and establishment year was 18 years, with the quickest field (Genetic Circuits) becoming established after 5 years, and the slowest (Clean Meat) becoming established after 63 years (the full list of times to establishment for the 8 fields, in years, is: 5, 16, 16, 17, 19, 26, 26, 63). Of the 2 non-established fields, at the time of writing one has had 31 years since its origin year, and the other has had 40.

Using a Kaplan-Meier estimator to estimate the cumulative probability of field establishment accounting for censored data (i.e. the fact that for Atomically Precise Manufacturing and Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence we don’t know how long it will be until they become self-sustaining, if ever), the mean amount of time between origin and establishment for the 10 fields we looked at is 31 years, with a 10% probability of establishment by 5 years, and a 90% probability of field establishment by 63 years. The full cumulative distribution function is shown below.

Note that these numbers are definitely not forecasts of how long after its origin year a “typical” field will become self-sustaining. One reason is that we generally chose fields that were associated with “big” technologies, which, for example, might mean that progress towards the technologies tends to be slower, perhaps causing the corresponding fields to become self-sustaining later than is usual for a “typical” technology field. Aside from this, taking the cumulative distribution function produced by the Kaplan Meier estimator at face value would seem to get you into trouble in at least some cases because, for example, we’d expect that there’s a non-zero chance that field establishment takes more than 65 years.

Still, if (for example) you think the 10 fields we look at represent a good reference class for the field you’re interested in, the above cumulative distribution function for time to field establishment might be useful for forecasting.

Opinionated stories about field establishment

Here are short, opinionated stories describing the main developments that led each field to become self-sustaining. These should be treated as speculative. They are attempts by us, as non-experts, to distill the key reasons the field became self-sustaining when it did.

This Google Doc contains these summaries alongside brief explanations of the choice of establishment year for each field. Notes on each field’s development that are more expansive but much rougher can be found in this Google Drive folder.

AI

AI research grew out of an interest in creating artificial brains and thinking systems, in part spurred by research in the 1940s which showed similarities between neurons and digital systems. The success of Enigma and rapid development of computing during WWII contributed to a general excitement surrounding the capabilities of computers and also prompted the US to invest heavily in machine translation, as well as other computing projects. Over this same period, small pockets of researchers interested in designing thinking systems had grown and become a bit more connected to each other, this (perhaps along with the discovery of an impressive algorithm) resulted in the organisation of the Dartmouth workshop. This workshop was the first time many of the researchers had met in person, unified the field and solidified the AI community.

Clean Meat

Clean Meat research became self-sustaining in large part due to the efforts of a few individuals who recognised that existing tissue engineering technologies could be adapted with some work to produce lab grown meat on a large scale. Jason Matheny in particular led the creation of the first influential paper on Clean Meat and was partially responsible for some of the first government funded research into the area. A few years later a public event was organised unveiling a prototype burger with the intention of selling the idea to the general public, this event received wide media coverage and made many more people aware of the concept.

DNA Nanotechnology

A lone champion (Ned Seeman) plugged away for 20 years, gradually discovering experimental techniques and structural motifs, and demonstrating impressive (though not practically useful) experimental products, until eventually (in the early 2000’s) the tools for fabricating and analysing DNA nanostructures were good enough that exciting things like DNA walkers and DNA origami could be fabricated. This prompted many new groups to join the field, and from there further results were impressive enough to at least ensure the continued growth of the field.

Fusion Power

In the 1920s and 30s, advances in theoretical physics resulted in an understanding that fusion reactions power the sun, setting the theoretical foundations for fusion reactor work. Fusion development was driven by the perception that it would be as fast and strategically significant as fission development had been in the 1940s. An early false report of controlled fusion caused multiple countries to assume that a race had already begun and they rapidly ramped up fusion research. Once it became clear that fusion was very difficult, other states were having similar problems, and the military significance of fusion had faded, fusion work was declassified and the field immediately coalesced.

Genetic Circuits

Genetic Circuits focused synthetic biology emerged as a field in the late 90s and early 2000s as a result of a gradual improvements in a few different areas in the 70s and 80s, such as: available techniques and supplies for working with DNA, a massive influx of new data on individual parts from newly developed high throughput sequencing, a more systematised understanding of cell parts and functions, and an injection of funding to explore this new area from government programs such as from DARPA in 1997. US government funding brought together interested scientists and resulted in two high impact papers which put the young subject on the map.

Quantum Computing

Interest in Quantum Computing became more widespread in scientific circles after a conference in which Richard Feynman and another scientist gave talks on Quantum Computing, the support of a prestigious scientist like Feynman was probably helpful. After this there was more interest in Quantum Computing but it was still relatively niche, however in 1994 Shor’s algorithm was discovered which attracted a huge amount of scientific and government interest. The security implications of Shor’s algorithm, perhaps along with some quicker than expected progress in constructing actual quantum logic gates, prompted the US government to publicly announce funding for Quantum Computing research which attracted further attention and research.

RNA Vaccines

In the early 90s mRNA therapeutics research was started by a strong initial result in mRNA delivery and was also probably spurred by the invention of PCR in the 80s, which allowed easy creation of large amounts of specific mRNA molecules. Progress stalled in the mid 90s due to the deadly side effects of mRNA delivery in animals, which led to a perception that the field had hit a dead end and was not worth funding, particularly when other DNA based gene therapies looked more promising at the time. Two scientists in particular doggedly pursued a solution to this safety problem for around a decade, eventually resulting in them solving it and opening the door to further therapeutics development.

Solid State Batteries

Once the advantages of solid batteries were recognised in the 1960s there were various somewhat promising but ultimately unsuccessful attempts at creating viable ones over the next two decades. In the 1970s and 80s there was a lot of excitement and effort going towards lithium battery development, and in 1978 scientists realised that lithium batteries in particular could especially benefit from being made solid. This realisation spurred intense efforts to develop solid lithium batteries, which resulted in the first fully solid battery being created in 1992.

Themes from reading about field histories

Here are some themes and other takeaways coming directly from our investigations into the histories of the 10 fields we considered for this project, rather than from (explicitly) considering the factors we recorded (many of these come from considering the “opinionated stories” shown in the previous section and their abbreviated versions as shown in this earlier section):

- In some cases, pursuing the technology seemed like a “no brainer” due to other recent developments (AI, Fusion Power).

- Quantum Computing stands out as the single case where a theoretical result dramatically changed perceptions of the importance of the technology.

- Military or other “strategic” considerations seem to be behind the beginnings of some fields (AI, Fusion Power, Quantum Computing); and, notably, these are the fields with the grandest / most distant goals.

- Recent advances in experimental techniques, theoretical understanding, or similar, seem to have been important in most cases; although “recent” might mean “in the last 5-20 years”, indicating that things often don’t move very quickly.

- The RNA Vaccines field experienced an unexpected setback before it became a self-sustaining field. It seems that work within the field showing how the setback could be overcome was important for allowing the field to eventually become self-sustaining.

- The fields in which individuals are noted for having had an outsized impact by fighting a lone battle over many years (Clean Meat, DNA Nanotechnology, and maybe also RNA Vaccines) are comparatively small / unambitious.

- The creation of a research community through conferences, talks, and research programmes is often a major milestone (AI, Fusion Power, Quantum Computing). These early events serve to grow the community, connect interested scientists, and establish a set of common foundations and aims for the young field.

- We often noted the involvement of US government funding in the early stages of a field. This was true for DARPA funding of AI in 1963, NASA work on Clean Meat in the 1970s and 1990s, heavy funding of Quantum Computing following the publication of Shor’s algorithm in 1994, and to some extent Fusion Power in the 1940’s and 1950’s (though the US was far from alone here); although note that we only used English-language sources which probably introduces a bias.

More details

This Google Drive folder contains all the public supplementary documents related to this project.

- An overview of the data collection process as a whole can be found here.

- Definitions for the origin year and establishment year can be found here.

- The full quantitative dataset, including the factors data and establishment year for each field, can be found here.

- The descriptions we wrote for each field’s development can be found here (brief and with an explanation for the establishment year choice) and here (longer).

- Additional, rougher notes on each field’s development, including development timelines, can be found here.

- Some “if I was free to speculate”-style thoughts from me on how to create a self-sustaining field can be found here.

A brief discussion of the correlations between factors can be found in the Appendix section called Correlations between factors, and a brief discussion of our attempt to develop a quantitative field establishment measure (an initially appealing avenue which we eventually abandoned) can be found in the Appendix section called We initially tried to develop a quantitative field establishment measure, but eventually decided not to.

Final thoughts

Neither Megan nor I currently have plans to continue with this work in the near future, but I think work in this area has the potential to be very valuable. I’d be interested in hearing from you if you’re interested in collaborating or otherwise taking this work further.

Directions for further work

Here are some directions I think could be interesting to explore for work in this area:

- Regarding data:

- Incorporate bibliometric data / scientometric approaches.

- Get higher quality funding data.

- Come up with a more systematic way to choose which fields to include in the analysis and / or collect data for additional fields.

- Explore options for crowdsourcing data.

- Define the factors and “self-sustaining field” more carefully and concretely, and do a more careful and thorough data collection.

- Revise the list of factors. For example: add factors in order to make the set of factors more comprehensive; revise factor definitions to increase the variance of the factors (i.e. the variance across observations within each factor).

- Make a simple, highly structured model for forecasting field establishment using factor count, time since origin year, and current values of 1-3 factors. Assess the model’s performance by testing it on some fields not involved in the model creation.

- Using the above model or other results from this project, make predictions about when fields of interest might become self-sustaining.

- Try longer-ranged forecasting, using factor count dynamics or otherwise.

- Try using different statistical and econometric techniques, such as formal causal inference methods, Cox regression, and other time series analysis methods.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank the many readers of earlier versions of this report for their feedback, including Ashwin Acharya, Hamish Hobbs, Jaime Sevilla, Nithin Sivadas, James Wagstaff, Max Daniel, Damon Binder, Michael Aird, and Adam Marblestone. We thank other members of the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI)’s Research Scholars Programme (RSP) for their thoughts and feedback on the project.

For this project, Megan was a research contractor at the Berkeley Existential Risk Initiative (BERI), as part of BERI’s collaboration with FHI. I did this project while on the RSP at FHI.

Appendix: more results

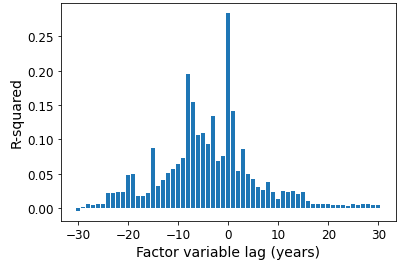

Plotting the logistic regression R-squareds against factor lag arguably provides weak evidence that our establishment year judgements are biased

In a section in the main text called Possible sources of bias and other issues, I mentioned that there’s a potential concern that a particular bias crept into the data collection process for the project, due to a possible (maybe unconscious) inclination to favour setting the establishment year to be a year where several factors switch on.

Some relevant evidence comes from this plot of logistic regression R-squared against factor lag for logistic regressions predicting establishment year from lagged factor count.

The data shown is for 61 different logistic regressions, each one regressing establishment year on lagged factor count. Each logistic regression uses a different lag for the factor count, between -30 years and +30 years. Note that here a positive lag corresponds to a factor count in “the past” and a negative lag corresponds to a factor count in “the future”. For example, the regression that uses a factor count with a lag of 5 regresses “was year Y an establishment year” against “factor count in year Y-5”.

The R-squared values are not very smooth, but there seems to be an underlying pattern where the R-squared peaks at a lag of around -5, corresponding to “using factor count to infer whether the establishment year was 5 years in the past”. On top of that underlying pattern there are some “spikes” where the R-squared at that lag is significantly higher than the R-squared values either side of it. Most notably, there is a large spike at zero lag.

Could this large spike at zero lag reflect a real effect? One real effect that might generate this spike is if there are often watershed moments where the prospects for the field suddenly change significantly. In fact, I think there are arguably examples of this for the fields we looked at, including: the 2005 publication of Kariko and Weissman paper’s for RNA Vaccines (illustrating a way to overcome a key problem holding back the technology), the positive public reception to the 2013 televised consumption of a cultured meat burger (demonstrating that there could be public interest in the product), or the 1994 discovery of Shor’s algorithm for Quantum Computing (suddenly the technology had striking defence implications) (though as it happens we set the establishment year for Quantum Computing to be 1996, the year the US government issued the first public call for Quantum Computing research proposals).

I think that, arguably, it makes sense for the establishment year to coincide with events like these. This could at least partially explain the spike at zero lag.

I still find the spike at zero lag a bit suspicious though, and partly because of this I’ve avoided presenting results that are very sensitive to our particular choice of establishment years in this report. In some cases I’ve presented results from the “lag 1” regressions, because I feel that this data is an okay compromise between having very biased data and throwing away the genuine information contained in our judgements regarding the establishment year.

Sensitivity analyses suggest that the logistic regression of establishment year against factor count is robust to exact choice of fields and establishment years

I performed some sensitivity analyses to get some idea of the robustness of the logistic regression fit of establishment year against factor count in the preceding year shown in the section called Factor count is positively related to whether / when a field becomes self-sustaining .

The plot below shows fits from logistic regressions of establishment year against factor count in the preceding year. Each multicoloured, transparent line corresponds to a fit with a randomly selected set of 3 out of the 10 fields dropped from the analysis (the plot contains 20 of these lines). The thick blue line shows the fit with the original data. The plot shows that randomly dropping 3 fields can have a reasonably large effect on the fit, but doesn’t qualitatively change the fit.

The plot below again shows fits from logistic regressions of establishment year against factor count in the preceding year, but this time the transparent multicoloured lines correspond to fits where bootstrap sampling was used to select the set of 10 fields (i.e. the set of 10 fields to use in the regression was randomly sampled, with replacement, from the true set of 10 fields; note that, as above, the plot contains 20 of these lines).

The preceding two plots show that the logistic regression fit of establishment year against factor count in the preceding year shown in the main text is fairly robust to dropping or resampling fields within the dataset.

The plot below again shows fits from logistic regressions of establishment year against factor count in the preceding year. This time, I applied random shifts to the establishment year. Each panel corresponds to a single regression. For each regression, I randomly shifted the establishment year for each field by an amount corresponding to a random draw from a normal distribution with a mean equal to 0 and a standard deviation equal to 3 years (each field was given a different random draw). In each panel, the orange line shows the fit with randomly shifted establishment years, and the green line shows the fit with the real data (the green line is the same in each panel).

The plot shows that randomly shifting the establishment years generally changes the fitted curve a bit, and probably also makes the fit a bit worse on average; but the effect isn’t too dramatic. This shows that the logistic regression fit of establishment year against factor count in the preceding year shown in the main text is fairly robust to randomly shifting the establishment year for each field by a few years, and so the apparent predictive power of factor count in the preceding year doesn’t hinge on the exact establishment years we chose when collecting the data.

The distribution of factor first occurrences within the breakout period isn’t just due to noise

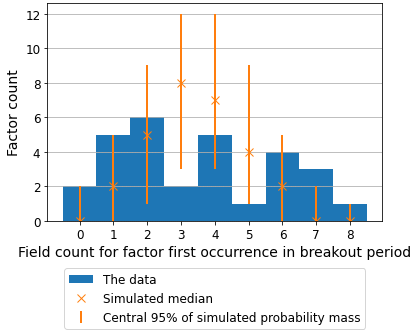

We define the “breakout period” as the period between the origin year (when the technology is first explored) and the establishment year (when the field becomes self-sustaining).19 One way to get a handle on whether the results shown in this report, especially those regarding the relevant effect of the different factors, reflect a real effect or are just due to noise is to see whether the frequency with which the factors occur within the breakout period is consistent with what we’d expect by chance (under certain assumptions).

To do this, I started by working out how often on average an arbitrary factor first occurs within the breakout period for an arbitrary field within our data. This turns out to happen roughly 44% of the time (note that I only considered data from the 8 fields we consider to have become self-sustaining, since we only know the endpoint of the breakout period for these fields). I then used simulations to calculate how many of the 29 factors you’d expect to have all 8 first occurrences within the breakout period (and similarly for 7 first occurrences within the breakout period and 1 outside the breakout period, etc), assuming that being inside the breakout period is something that happens with 44% probability irrespective of the identity of the factor or field (or in other words, what you might expect to happen “just by chance”). The results are shown below, alongside our actual data.

The number of factors with 8 or 7 first occurrences in the breakout period is at or above the 95% confidence interval in both cases.20 The number of factors with 6 first occurrences in the breakout period is also substantially above the simulation average. The results for the lower tail (0 or 1 first occurrences) are similar. This should provide some confidence that the results shown in this report are not purely driven by noise.

As for the identity of the factors that most often occur within the breakout period: “early prototypes exist” first occurs within the breakout period for all 8 fields; “risk tolerant funding”, “well connected networks”, and “practical designs exist” first occur within the breakout period for 7 fields; and “powerful people want technology”, “high perceived impact”, “practical work exists”, and “high profile paper exists” first occur within the breakout period for 6 fields. Maybe unsurprisingly, these factors are similar to the ones identified by eye as tending to occur in the run-up to field establishment in the section called When the different factors tend to occur.

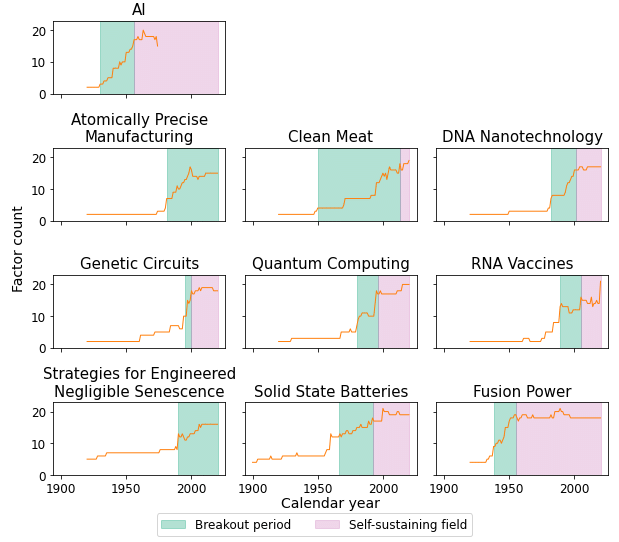

Factor count dynamics

I’ve plotted the time series for the factor count for each field below. The green shaded region shows the period between the origin year and the establishment year (the “breakout period”), during which we consider the field to not yet be self-sustaining. The violet shaded region shows the period during which we consider the field to be self-sustaining (although note that we focused on specifying the start of this period and didn’t worry too much about whether it ended at a later date – for example, maybe you could argue that the field of AI was no longer self-sustaining at some point between 1960 and 2000).

Interestingly, it seems to me that the factor count generally shows some kind of trend, and so it should be possible to forecast future factor counts using past factor counts with at least some degree of accuracy.

Investigating factor importance with decision trees

In a similar spirit to the lagged logistic regressions described in the section called Results from statistical measures of factor importance, I investigated which factors are important for field establishment by fitting decision trees. As was the case for those logistic regressions, I used “is year Y the field’s establishment year” as the outcome variable, and the factor values for a given year Y-A as the regressors, for various values of A. I fitted decision trees with a maximum depth of 2, which allows the decision tree to select up to 3 regressors.

Analogously to the plot shown for the logistic regressions in the main text, the plot below shows the factors selected by each decision tree for the corresponding lagged factors.

For example, at lag 0, the decision tree uses “high perceived impact” and “early prototypes exist”. These two factors were also selected by the logistic regression for lag 0 factor (alongside another factor, “strong results”).

As noted in the main text, “commercial products exist” is an example of a factor that is selected at several lags by the decision tree but isn’t selected at all by the logistic regression.

Correlations between factors

Top pairwise correlations

The top 10 correlations between factors mostly consist of correlations between 2 groups of 3 factors: “well connected networks”, “risk tolerant funding”, and “sense of possibility” are highly correlated with each other; and similarly, “practical designs exist”, “early prototypes exist”, and “practical work exists” are highly correlated with each other (the correlations are roughly between 0.76 and 0.88). In addition, “risk tolerant funding” is highly correlated with the factors in the second group, and “high profile paper exists” is highly correlated with “high perceived impact”. The high correlations mean that these factors tend to move together, and in particular for our data probably means they tend to switch on at roughly the same time.

You might wonder whether the time series are such that we can tell a story where “risk tolerant funding” tends to precede (and so, maybe, cause) the “practical” factors in the second group. Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the case in our data; the order in which these factors switch on for each field is fairly mixed.

Still, it seems interesting that there are these two groups; you might say that group 1 corresponds to “signs that work will be done in this field” and group 2 corresponds to “practical progress in this field”. According to the data, factors within each group tend to happen together.

Negative average correlation

The only factor with a negative average correlation with the other factors is “no scientific pushback” (with an average correlation of -0.08). This suggests that, broadly speaking, “no scientific pushback” tends to switch off when other factors switch on; and it seems plausible that increasing progress / prominence of a field is associated with an increased chance of mainstream scientific pushback.

We initially tried to develop a quantitative field establishment measure, but eventually decided not to

We originally planned to develop a quantitative measure determining when a field is self-sustaining, so that the establishment year would be determined objectively rather than being down to our subjective judgement. We thought this could be based on (some combination of) how funding, paper counts, Google Ngrams, or patent counts evolved over time.

However, funding data seemed very difficult to obtain, Google Ngrams were easy to obtain but didn’t seem to capture what we were interested in, and meaningful patent counts seemed hard to obtain.

Paper counts

Paper counts were relatively easy to obtain (as long as you’re not too worried about getting exactly the right papers) through (for example) Web of Science, and seem more closely related to field development than Google Ngrams. However, in the end we weren’t able to find a quantitative rule we were happy with for a field becoming self-sustaining based purely on paper count.

One issue with using paper counts is that it’s hard to find search terms that will capture the papers within the field of interest: there are often a large number of false positives (i.e. papers appearing in the search that have nothing to do with the field of interest), and there are probably also many false negatives (i.e. relevant papers missing from the search), especially early in the field’s development (which might be an important period!) where the standard terminology for the field hasn’t yet been established. The proportion of false positives and false negatives doesn’t seem to necessarily be consistent across fields.

More fundamentally, it seems like it might just not be possible to capture what we mean by a “self-sustaining field” with paper counts, even with search terms that bring up exactly the right set of papers.

However, we are not experts at assessing the state of a field using paper counts or other quantitative metrics, and it seems very possible that a more experienced researcher or a more thorough attempt might yield good results here. This seems especially true if the quantitative metric only needs to loosely track what we mean by a “self-sustaining field” in this project.

Notes

-

See this Google Doc for a list of the factors and their definitions. ↩

-

For example, maybe the two non-self-sustaining fields we chose reflect our exposure to the EA, rationalist, and futurist communities, making these “atypical” in an important sense. See this section for more discussion. ↩

-

Roughly: “from when the field started existing to when it became self-sustaining”; see this section for more detailed definitions of “origin year” and “establishment year”. ↩

-

Technology Forecasting, Science and Technology Studies, and Innovation Studies seemed potentially relevant but we weren’t able to find much literature in these areas addressing the question of how academic fields emerge. A commenter on an earlier draft also mentioned Management, as well as Science Policy (example papers: An economic evaluation of the war on cancer, The relation between R&D spending and patents: The moderating effect of collaboration networks), which seems potentially relevant but which we didn’t investigate closely. ↩

-

Relevant work in this area includes Identifying emerging topics in science and technology, A novel approach to predicting exceptional growth in research, and Machine Intelligence for Scientific Discovery and Engineering Invention. ↩

-

I use “binary” here to indicate that each variable at a given time could take one of only two values (i.e. it could either be “on” or “off”), as opposed to, say, being graded on a scale of 1 to 5. ↩

-